In mid-2017, a few months after I had moved to Delhi to work for a national newspaper, I began to browse job websites. Every other day, an Indian news report underlines the gap between jobs and jobseekers. In 2016, in one municipality, 19,000 people applied for 114 jobs; among those competing to be a street sweeper were thousands of college graduates, some with engineering and MBA degrees. In the same year, more than 1.5 million people applied for 1,500 jobs with a state-owned bank, and more than 9 million took entrance exams for fewer than 100,000 jobs on the railways.

Faced with this lack of opportunity, many turn to rioting. Within months of returning to full-time reporting, I had covered two large urban youth revolts, in which entire cities had been shut down as people demanded quotas in education and jobs – today, young people from agricultural castes want to work in offices and not farms. I wondered what other options were open to them.

Then, while scanning jobs websites one day, I saw the ads: a mix of keywords that seemed designed for the ambitious young jobseeker: “International BPO. Zero years’ experience. 40% ENGLISH required. ONE-DAY training. Fast CAREER Growth – a LIFE is what you make.” In 2017, a call-centre job at a BPO (a business process outsourcing company) doesn’t have the appeal it did a decade or so ago. The industry has lost value over the years because of poor oversight, and competing markets including the Philippines and US prisons. But it’s still a job.

At the bottom of such job adverts is the name and number of an “HR”, a middleman between a jobseeker and a placement agency. One day, a colleague and I called one of them. The middleman wasn’t interested in knowing anything about us – he simply told us to expect a text message after the call, and to follow the instructions. The text invited us to an interview at a recruitment office in west Delhi, where we were supposed to hand over the code at the bottom of the message.

The next morning, we went to the address, which was in a business centre in an unfashionable part of the city. Our interviewer – a woman wearing a sequinned green kurta, dark brown lipstick and brightly painted nails – told us to introduce ourselves, and we obliged in our best “40% English”. I was a high-school graduate from Uttar Pradesh for the day, and my colleague was posing as an equally qualified cousin.

The interviewer asked us how much success mattered to us. We said our lives depended on it. She said we weren’t ideal candidates – she was not satisfied with either our English or our confidence – but she was going to offer us jobs anyway.

Using the back of one of our fake resumés, she wrote down a jumble of words that followed up on the promise of the ad: “International exposure, night shift, 20,000 rupees [£232] salary, 30% increment every three months.” She even gave us a slip of paper confirming our employment: “We are pleased to inform you that you are hereby selected for CCE (Customer Care Executive) in the BPO department of our organisation.” The slip did not state the name of the organisation.

Unlike most jobseekers who come to these agencies, we pushed our interviewer for details of the company we had been hired by. Irritated, she blurted out a name, but nothing else. When can we join the company, we asked. Next week, she said. But before that, we would have to go to another part of town for our one-day training – details to follow in another text – and before we left the room, we had to give her 500 rupees each for coming this far along.

The text message came in as promised, and directed us to an even more obscure address in south-east Delhi for the “training”. When we arrived, we queued up and paid 1,000 rupees to enter the classroom. We sat down and were asked to introduce ourselves by our trainer, a young man in a snug T-shirt, loose jeans and spiked hair. He then pointed out numerous flaws in our speech and confidence. He gave us a formula for the perfect introduction (“your name, where you are from, where you live, your education, your experience, and your hobbies”) and the best way to end it: “Thank you. That’s all about me.”

Spoken English is key to a call-centre job, he reminded us. He said there was no word in English he couldn’t pronounce: “Zoo, Alpha, Nancy, pleasure, treasure, vision.” He went on: “My father went to zoo and we saw green dinosaur. My favourite movie is Prince of Persia. It’s my pleasure to have treasure.” When he had finished showing off, he told us all about his personal journey, from a village in Bihar to a call-centre in Gurugram, a technology hub just outside Delhi. “It doesn’t matter where you are from if you have a plan,” he said. Someone in the class asked him what his plan was. “I work for money,” he said. “Career should follow money.”

Later, I would remember one of the first things he had said after entering the class. “How many of you know the meaning of ‘manipulate’? Have you ever taken someone for a ride?” By the time he was done, most people in the class looked baffled by how little they had learned about their jobs in spite of paying handsomely for the training. All they wanted was to start the jobs they had been promised. But we were then led to another floor, divided into groups and sent for a fresh round of interviews.

This time we faced actual representatives of companies interested in hiring us. When it was my turn, I told my interviewer that I had already been hired by her company. She said she would still like to be sure of something. “Sell me this phone,” she said, pointing at the mobile phone in my hand. I did my best to expound on its battery life and camera. After challenging my colleague to the same task, she said we should wait for a call from the company.

Many jobseekers leave their training with appointment letters asking them to report to work the next week. These letters never mention the name or address of the company. Everyone is told to expect another text message with further details. One young man we met that day, Pradeep Saluja, left the building thinking that he was about to start working in customer service for Amazon, as the job ad had promised.

When I called him a month later, Saluja told me that the job had in fact turned out to be in a small office with a strange name, in Gurugram. He was given a script to memorise and asked to get on the phone, along with 50 other “executives” of a similar age.

The job was easy, he said. All he had to do was call people in the US from a list, introduce himself as Charles, and tell them they were under federal investigation for tax evasion. One out of 10 people would freak out, he said. At the first hint of panic in their voice, Saluja told them he was going to transfer the call to a different department, where one of his seniors would help them pay their taxes through an online money transfer.

Saluja didn’t like the company’s work culture: the hours were long and the targets unrealistic. He quit the company after three weeks and went back home.

So you were working for a call-centre scam, I suggested to him. “You could say that,” he said. He told me it wasn’t a terrible gig for someone truly in need of a job. He asked me if I had got one yet. I said I hadn’t. Within five minutes of ending the call, I got a message from him with the number of the company’s HR.

Six months before I met Saluja, the police raided a seven-storey call centre in Mumbai and arrested hundreds of youngsters for posing as officers of the US tax office and cheating people out of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Two months before the raid, two employees of the call centre had contacted the Federal Trade Commission in Washington to tip them off. I spoke to one of the whistleblowers, 19-year-old Pawan Poojary, on the phone. He hadn’t always hated his job, he told me. He had joined the company knowing he would be a scammer. He was a college dropout looking for a way to make “lots of money”. One day he got a call from an HR who had seen his resume on a jobs website and thought he was perfect for a job.

After Poojary came in for an interview, the company appointed him as a “closer”, the person to whom an “opener” such as Saluja passes on a call after the introduction. The salary was 15,000 rupees (£175) a month, plus incentives. “Whatever I made in dollars in one call, I would be paid twice the amount in rupees,” Poojary told me. In other words, he kept less than 1/30 of the take. He says he was asked to come for training the next day.

The trainer started by asking the 10 new recruits if they had heard of the IRS. He spelled it out for them. Everyone shook their head. “Then he explained that we were going to call Americans [pretending to be] the IRS,” Poojary told me. “The moment he said this, I knew something was wrong. I asked him: ‘Is it a scam?’ He said it was, and told us that if anyone had a problem, they could leave. Only two people left.” The remaining eight were given a six-page script.

It went like this: “My name is Paul Edward and I am with the department of legal affairs, with United States Treasury department. My badge ID is IRD7613. We called to inform you about a legal case filed under your name by Internal Revenue Service under which you are listed as a Primary Suspect.

“Now I want you to grab a pen and a paper so I can provide you with your case ID number: IRC7647. Now I even have a legal affidavit against you, which is issued by the Internal Revenue Service. If you allow me, I can read the affidavit to you, so that you will come to know what your case is all about.”

Poojary read it out to me in his best American accent, which he had perfected by the end of his first week. He insisted that I play along as the unwitting American. No matter what I said, Poojary had a readymade response from a list of “rebuttals” in the script, including the line that settled the matter once and for all: “The police department, along with our IRS investigation officer, will be at your doorstep within 30 minutes.”

“Many people started crying on the phone,” Poojary told me. When that happened, he would ask them to drive out to their nearest department store and buy an Apple gift card worth hundreds of dollars. He would then transfer the call to a senior who collected the code on the back of the card.

Poojary loved it. “I was having so much fun,” he told me. And he was good at it: in just two months, he “earned” $24,000 for the company. He was thrilled at his ability to scam Americans, who, according to his friends and colleagues, considered themselves superior to the rest of the world. Like most young employees of the company, he wanted to live it up like the mastermind of the scam – a 23-year-old man who drove luxury cars, owned big houses, travelled business class and dated beautiful women. On his birthday, Poojary was given 50,000 rupees (£580) in incentives. “I blew it all immediately,” he said.

But by the end of the same week, he decided he couldn’t do it any more. “I was on the phone with an American lady from California or Texas. I told her the script. She started crying. She said she had no money, that she was about to go to a food bank to get her son something to eat. I felt miserable. I was like: ‘How would I feel if someone did this to my mother?’” Poojary put her on hold and told his supervisor he couldn’t go through with that call. “It didn’t matter to him. He took the call over from me and carried on.”

For thousands who end up at scam call centres in cities across India, impersonating tax officers, loan agents, Apple executives or cut-rate Viagra manufacturers, the job provides the thrill of cracking the code of American emotions. It is often these young Indians’ first experience of dealing with foreigners – scam call centres prefer to hire outsiders who are new to the big city – and their success depends on how well they understand the weakness of the people on the other side.

These are just some of the broad range of insights I have heard from current and former scammers:

“America is full of old people who live alone. They have no one to turn to if anything goes wrong.”

“In the US they don’t like to fix anything by themselves. If they have any issue, they will call customer care. This dependence is their main problem.”

“In America, they are very particular about their privacy, their security, their individuality.”

“It’s very easy to scam Americans. They are very gullible.”

This sociological wisdom powers a large chunk of the economy in satellite cities such as Noida and Gurugram, where entire districts are dedicated to call-centre scams.

“The best part about these places,” said Vikas Tanwar, an ex-scammer, “is that you can easily get a job.” In what other place, he asked, would someone like him – just another jobseeker with a bachelor’s degree from a smalltown college – receive a call from a company telling him that he perfectly matches their requirements? Some young Indians shuttle between con jobs for years, telling themselves they will quit after just one more month’s salary.

In 2016, Microsoft published a global survey showing that two in every three people had been exposed to a tech-support scam in the preceding 12 months. Americans lose around $1.5bn to tech-support scams every year; 86% of them originate in India. They usually involve infecting a computer user’s web browser with a pop-up message that tells them their machine has been compromised, and the only way to save it is to call this number. The person who picks up recites a script, asking the panicking caller for remote access to their computer. Once connected, they present regular files as deadly threats. “We also run fake software on the computer to make up viruses, trojans, malware. Then we tell them that if they don’t buy our security products – $299 for a year, $399 for two years – the computer will become unusable,” said Tanwar, who worked on a tech-support scam alongside 500 others at a call centre in Gurugram. His brief was to make $500 from every call, and his incentive was 1,000 rupees for every $1,000, or 1.5% percent of the take. “The moment you put on your headphones, your supervisor tells you: ‘You are scammers. You have to trap the customer, no matter how,’” he said.

Tanwar didn’t mind the job that much, but was enraged by the company’s denial of incentives. For Abhishek Singh, an engineering graduate from Kanpur who worked in the same call centre for two years after moving to Delhi, the guilt came much later. “There would be nothing wrong with their computers. The whole thing was a scam. You get remote access, then make up whatever stuff and charge them $400 or $500. The more you fuck them over, the better. Most people who get pop-ups are doing something wrong – porn or illegal downloads. But what we did was wrong because the software we sold them is freely available on the internet.”

Singh told himself he was going to quit the company after the second month’s salary. He did, but soon realised the only other job he could find was also working a scam. Singh was trained to upgrade his scare tactics at this company: “Even the FBI was involved if the customer refused to pay, and as a final blow, we told them that Homeland Security would be informed, and their internet would be cut off and they would be blacklisted. They paid anywhere between $200 and $2,000, sometimes through Apple gift cards.”

It’s often just a matter of time before the new recruits forget their life goals and start to thrill in their ability to pull off a scam. “Everyone thought they were characters from Wolf of Wall Street,” said Singh. “People turned up at work high on weed. Everyone abused each other across the floor for not being able to cheat like a pro.”

And before they even know it, their ideas of right and wrong become blurry. “Whether it’s fraud or not depends on perspective,” said one young man who has spent five years conjuring up viruses on healthy computers. There’s one particularly popular justification scammers give themselves when torn between money and morality: as young men with no prospects, they are the biggest victims – and the whole world is a big scam.

For some, the question of ethics had been settled the moment they decided against mediocrity. “In Delhi, you can’t become an important man without pulling some kind of fraud,” Sunil Kumar, a recruiter for scam call-centres, told me with a smile. I met him while posing as a jobseeker at a training centre. A lanky, long-haired 26-year-old, Kumar moved to Delhi from a village in Uttar Pradesh eight years ago. A school dropout, he started his career supervising security at a shopping mall, but quickly moved on to fixing low-level jobs for youngsters arriving in Delhi from his village.

These days, by his own reckoning, Kumar is an important man. He makes 150,000 rupees (£1,740) a month and employs eight people. His employees trawl CVs on jobs websites to identify anxious jobseekers, and are paid according to how many they can lure to the agency. “I charge commission from companies: 2,000 rupees (£23) for placing one kid,” Kumar said. He usually ends up placing more than 50 every month.

I asked him if he ever felt responsible for what the “kids” are made to do. But the profit margins in his business are too big for anyone to care. “See, every call centre is engaged in one or the other kind of fraud. You can’t do much,” he said, avoiding eye contact. Still, he has tried to think through the implications of helping to staff scamming groups, even if only to save his skin. “If [jobseekers] call you and complain that they are made to take part in a scam, you say: ‘Is that so?’ You try your best to act in their interest. You say: ‘Why don’t you stick it out until the end of the month and get out after collecting the salary and join another company?’”

This way, he said, he can kill two birds with one stone. Not only has he shrugged off his own responsibility in the matter, he gets to keep a captive pool of kids to peddle. Kumar’s business thrives on the fact that scam call centres are always short of employees. When we talked in June 2017, Kumar said he had 2,500-3,000 openings to fill.

We were sitting in a coffee shop in Noida, and he was asking me to stop looking for a job and start thinking big. “What’s the point? My father worked the same job his whole life. When I went home recently, I asked him: ‘Was it worth it?’ I told him that I don’t work for anyone, but I can claim the respect of at least 500 people.” Kumar said he didn’t even have to work anymore to earn his income; the money just kept on coming. He devotes his extensive free time to his two passions: dancing and playing cricket.

Four months after we walked into the placement agency, my colleague and I had still not heard from the company we had interviewed for. One day we searched for its name online. It did have a website; a slideshow on top of the homepage featured the skyline of Manhattan as well as smiling, confident Americans holding meetings and striking deals. The description of the work it did was vague – redefining perfection, exquisite product service delivery, and so on. There was no way of telling what this exquisite product was, or to whom this service would be delivered. There was also a list of the company’s clients, but none of those names returned any useful search results.

We decided to turn up at the address and claim our right to a job, for which we had already paid 1,500 rupees each. At the reception, a small space with lockers, a saggy black sofa and anti-drugs posters on the walls, we informed a security manager that we needed to see someone in the HR department. We were handed application forms and asked to wait to be called for interview. Unable to convince the man that we had been through the process already, we filled in the forms again and waited to be called into the call centre, the tinted-glass door of which was being guarded by a gun-toting bouncer.

I was called in first. A woman behind a table was looking at my CV and circling entries with a pen. I told her that I had an appointment letter from a placement agency confirming this job. She said it meant nothing. “Can you sell me this phone?” she said, tossing her own on the table. I repeated my past performance, word for word. She asked me to follow an usher to the next interview. This time, I sat across a table from two suited men, and made a sales pitch for a mobile phone again. After my colleague was put through the same drill, we were told to leave the building and wait to hear from the company.

By this time, I had been interviewed for this job four times, and was intrigued to discover what I would be selling, if I ever got in. One day I found the online profile of someone who mentioned the company’s name as a previous employer. I sent her a message on Facebook, and she replied to say that she was glad someone saw the mention. “I wanted people to know what the company is all about,” she said.

Sona Kapoor, 23, came to Delhi from Uttar Pradesh in 2016 and joined the first company that offered her a job. It seemed like a regular call-centre job until, at the end of her training on the first day of work, she was handed a script. For two months, Kapoor called nearly 50 people from a list every day – Indians and Indian migrants to the Gulf countries – always opening with the same line: “Do you want a job or a job change?”

If they said yes, she directed them to a jobs website and told them to register their profiles, at a cost of 4,000 rupees. Then she transferred the call to a closer, who would offer a suite of career-boosting services – designer resume, social media profile builder, live interview preparation etc – crafted to close any remaining gap between them and their dream job.

“No one ever got any job. Nothing was what it seemed to be. Everything was a lie,” said Kapoor, who learned the truth about her job within a week. “If clients called back threatening to file a police complaint, the company refunded the fee, but we got only four such calls every day.” I asked her why she participated in the scam while fully aware of what she was doing. “You think because the people who run these call centres are making so much money every day, you might as well make some of it while you are here,” said Kapoor.

The way to scam Indians at such a scale, apparently, is to promise them jobs – the fulfilment of their most cherished dream. At least some of those responding to ads promising mass openings and unlimited incentives will end up landing a job – even if that job is just to scam other jobseekers.

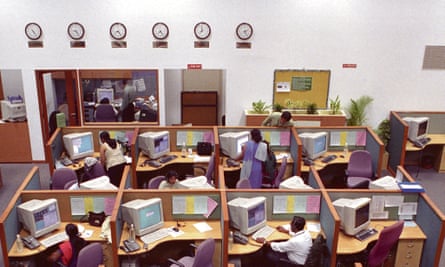

Main image: a view over Noida, a satellite city of Delhi. Photograph: Alamy

Some names have been changed. Adapted from Dreamers: How Young Indians Are Changing the World by Snigdha Poonam, which will be published by Hurst on 11 January.

To order a copy for £14.99 go to guardianbookshop.com