‘Jingle Bells’: A Racy Drinking Song (for Thanksgiving)

On the uncertain history of the first song to be broadcast from space

Welcome to The 12 Days of Christmas Songs: an attempt to uncover the forgotten history of some of the most memorable festive tunes. From December 14 through 25, we’ll be tackling one secular song and one holy song each day.

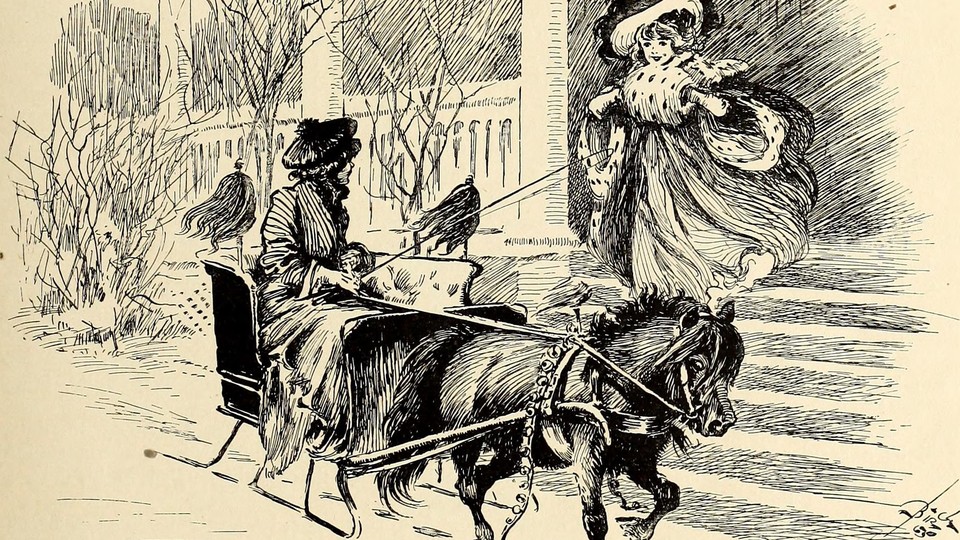

“Jingle Bells”: It’s the most wonderful song of the year (maybe). There are bells on bobtails ringing, and horses dashing through snow, and spirits made bright, and laughter galore. Its tune and lyrics are synonymous with Christmas, not to mention the sound of sleigh bells, which are so festive at this point that everyone from Eels to Low throws them into their indie Christmas jams.

There’s only one problem: “Jingle Bells” doesn’t mention the word Christmas. And according to the checkered history of the song and its composer, it was written for Thanksgiving. As a drinking song. And a Sunday-school song. And a jaunty tune about frolicking with ladies. Written in Massachusetts. And Savannah, Georgia. By a Bostonian who lost all of his money in the California gold rush, and who followed up the success of “One Horse Open Sleigh,” as his magnum opus was then known, by writing battle songs for the Confederacy, even though his father and his brother were both abolitionists.

Not all of this can be true, of course, although the last part is perhaps the most reliable. “Jingle Bells” is attributed to James Lord Pierpont, who was born in Boston in 1822 and grew up in New England. His father was a reverend and a poet; his uncle was the financier John Pierpont Morgan, better known by his initials, J. P.

Pierpoint Jr. was something of a wayward youth, running away to join a whaling ship, and pursuing various ventures during his life, most of which were unsuccessful. “Jingle Bells” is his undisputed greatest professional achievement. The Medford Historical Society claims that in 1850, Pierpont composed the song “Jingle Bells” in the Simpson Tavern in Medford, Massachusetts. Savannah, for what it’s worth, also claims ownership of the song, and it was indeed in Georgia that Pierpont first published the song in 1857, and where it was reportedly first performed at a Thanksgiving Sunday-school service.

But here, again, it gets sticky. The original lyrics of “One Horse Open Sleigh” are a little, well, racy. The second verse, for example:

A day or two ago

I thought I’d take a ride

And soon, Miss Fanny Bright

Was seated by my side,

The horse was lean and lank

Misfortune seemed his lot

He got into a drifted bank

And then we got upsot.

Upsot! And the fourth verse:

Now the ground is white

Go it while you’re young,

Take the girls tonight

And sing this sleighing song;

Just get a bobtailed bay

Two forty as his speed

Hitch him to an open sleigh

And crack! You’ll take the lead.

“Go at it while you’re young!” It’s difficult to imagine fresh-faced children singing this for a Unitarian Thanksgiving service in the 1850s. Funny, but difficult. There are also claims that “Jingle Bells” was a popular song to drink to in the 19th century, and that guests at parties would “jingle” the ice cubes in their glasses while they sang along.

What’s certain about the song is that its big moment came in 1943, when Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters recorded a version so popular it’s still played at Christmastime now. More to the point, Barry Manilow has covered it. And Bart Simpson, albeit with slightly different lyrics.

So the next time you hear “Jingle Bells” in church, or at a holiday party, or on the radio in one of its several thousand popular renditions, it’s worth remembering the uncertain history of the song, its fast-and-furious imperative, and how things worked out for James Lord Pierpont, who died at the relatively senior age of 71 in Florida, far away from the snowy sleigh rides of his feckless youth. Seven decades after his death, the work he’s best known for became the first song to be broadcast from space. Dream on, dreamers.